This week's readings focused on the consequences of the digital revolution and within that sphere the creation and use of digital photography.

The most negative viewpoint on digital photography was Fred Ritchin's writing titled

After Photography: Into the Digital. He begins his discussion with the digital revolution and how it has created a space where "touch is reduced to clicking and sight to a rectangle." This rectangle has become a world unto itself or an uberenvironment that has consumed the user in its menagerie of digital media.

According to Ritchin, digital media is always malleable in that it can always be rethought and reconfigured, and is more pliant to human will than perhaps any other medium before it. It is all at once nonlinear, made up of code or data, which is constantly being manipulated, has multiple authors, circumvents nature while redefining space and time, allows the original and the copy to be the same thus draining the original of meaning and is interactive. All of these items are in some form of opposition with what photography used to be. For example, analog photography was understood as capturing a specific moment in time where whatever was photographed was understood to be real. For Ritchin, this credibility of the realness of photography is what is in jeopardy with the development of digital media.

What has taken the place of reality is virtual reality, a created reality. This "reality" is based on the image rather than the actual experience. We desire the image more because it is unreal. This unreality seems to us to go beyond our finite existence and so we want it more.

|

| The Most Photographed Barn in America |

To explore this point further, Ritchin includes an excerpt from Don DeLillo's

White Noise. In it DeLillo and another man named Murray drive out to see "The Most Photographed Barn in America." Once there Murray declares, "No one sees the barn." and "We're not here to capture an image, we're here to maintain one." In other words, society has decided what the barn looks like and so that is the way everyone sees it. Everyone who goes and sees that barn is actively perpetuating the illusion or image of the barn, not the actual real barn. They do not experience the bar, they capture it, flattening it out to be shared with others.

In the end Ritchin, almost desperately, asks "Where is the real now?" He offers no answer here, but it almost seems hopeless that it will ever be found again. We are looking at pictures of pictures, everything is manipulated and made into whatever whoever wants it to be. In this time, the real seems to be only found in its always shifting form- the unreal.

In opposition to Ritchin's writings is Corey Dzenko's

Analog to Digital: The Indexical Function of Photographic Images. Basically Dzenko argues that the reliability of photography has not changed despite the digital revolution but rather it "enlarges" the traditional practice of it. He cites the fact that digital photography has visually taken cues from its predecessor, analog photography, in order to maintain the belief that the photograph represents reality and because of these cues (characteristics and conventions of the real) the viewer sees the "real."

|

| Kerry Skarbakka, Stairs |

For example, he uses the work of Kerry Skarbakka, specifically an image titled

Stairs. Here, the artist used digital technology to make it appear as though he is falling down the stairs. He then posted this image on FailBlog.org and to not much surprise people commented on the image as though it had really happened. This is because the photographic appearance of the image, created by Skarbakka through the study of analog photography, and the context surrounding the display of the image all led to its credibility as something that really existed.

Dzenko also brings up the point that the believability of photography has always been something that has been in question, since its beginning. This question of reality is not something new in photography and as such is no cause for alarm. The question has remained and viewers have believed.

The final point he makes is that the social uses of photography have generally been ignored as part of this discussion. He sees the digital as just replacing the analog in social use. For example, when looking at an image in the newspaper, he gets the same information from it as he would if he viewed it online. Fundamentally he believes that there is no difference, socially, in viewing the image one way or another.

The final article, Jorge Ribalta's

The Meaning of Photography, rewinds the argument of digital photography's consequences to a recontextualizing of the understanding of photography in the post-modern age. In order to get into the digital we first have to understand that photography died along with the modern utopia, during the modern age. These deaths correspond with the shift from analog to digital and that it is precisely the digital that has allowed the reappearance, even if it is disembodied from its original form, and explosion of photography into our visual culture, or in Ribalta's words "photography dies but the photographic is born."

Ribalta also questions, but does not directly refute, the idea that the digital photograph, with its loss of the indexical value of the sign, means that it also looses its believability. He does recognize that, yes the digital has relaxed the relationship of the photographer to the photograph by making it easy create and dispose of but like Dzenko, she also notices that the digital uses the "codification and simulation of original photographic procedures." She goes beyond Dzenko though in that for him realism is now an effect, something to be created, a normalization of the digital image into the photographic sign.

Since realism is the the power and status of photography, Ribalta then begs the question, "Can photography maintain social relevance in the era of crisis of photographic realism?"In response to this he outlines his idea of molecular realism, or a realism that combines documentary and fiction. He argues that with micropolitical discussions between the author and the spectator and a radicalization of the institutional critique, this new hybrid realism is possible.

In supporting these two branches of his plan, Ribalta discusses artist Jo Spence and the Barcelona Survey. With Jo Spence he discusses her ideas of democratizing the meaning of imagery through the understanding that now anyone can access the same tools as professionals. It is this democratizing that will show a resistance to the refined status of the art object. As this refined status lies with institutions, Ribalta calls for such institutions to reconsider moving beyond cultural confinment and modernist notions. He asks for a radicalization of the institutional critique so that we can begin to understand digital photography through the reinvention of documentary and photographed realsim, or his molecular realism.

In the future, Ribalata hopes that all of this is possible, so that we can move on into the new potentials that are arising out of these relationships between politics, social sciences and art.

In synthesizing all of these readings I am more inclined to agree with Ribalta's ideas. It seems to me that a rethinking of the way we describe and work with digital media would certainly be beneficial, specifically if we were able to move beyond the modern.

I, along with Ribalata and Dzenko, do not really believe Ritchin's view that the credibility of the photograph is at greater risk now. This has always been a question in photography and so now, even though digital photography is different, given all of Ritchin's reasons, people as a whole, through digital photography's appropriation of names and conventions of analog photography, still believe in the photograph as real despite numerous questionings throughout history.

Another thing is that photography has been able to be manipulated since its beginning. I understand that now manipulation is now much easier and thus does not require a master, but manipulation such as what occurred in the Cottingley Fairy photographs. In these photographs two young girls, Elsie Wright and Frances Griffths, convinced a good number of people that the images they had taken were of real fairies. They later admitted that the fairies were card board cutouts, but because of the power of the photograph, people believed, even though it seemed quite impossible. Despite this trick, and many more, people continued to believe in photographs. This fakery in the image happened in 1917, long before the digital revolution, and would continue to occur throughout photographic history.

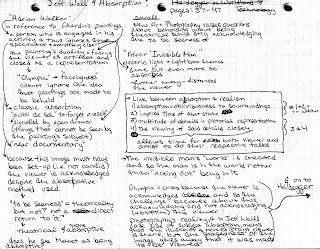

Perhaps the most widely known photographer who uses digital manipulation in order to normalize his digital images into appearing as analog photographs is Jeff Wall. Everything Wall does is what he calls "near documentary" and what is meant by this is he constructs his digital images in such a way that they appear to be not constructed.

An example of how he makes it appear as though the digital is analog, and thus leads the viewer into believing the image, is in his image

Morning Cleaning. Here, if Wall had wanted to, he could have brought out detail in the dark carpet where the legs of the chairs are. Instead, he let them drop off into it, as if he had just taken this one frame in one moment, instead of hundreds over several days.

|

| Jeff Wall, Morning Cleaning |

Overall, I do not believe there should not be such a great concern with how digital has affected belief in photography. I believe that he digital revolution is still so very young that now is not the time to act but rather to observe.

For me, this is where George Baker's Photography's Expanded Field feels apropos. Baker, who is interested in photographic forms that signal the end of the medium, has discovered that photography has both dispersed and returned to and from the potentials of photography in ways that almost leave behind the original medium-specific notion of the photograph. It is this "expanded field" that Baker attempts to map out with little success, as the medium's moves are so multitudinous and quick.

For me, this is where George Baker's Photography's Expanded Field feels apropos. Baker, who is interested in photographic forms that signal the end of the medium, has discovered that photography has both dispersed and returned to and from the potentials of photography in ways that almost leave behind the original medium-specific notion of the photograph. It is this "expanded field" that Baker attempts to map out with little success, as the medium's moves are so multitudinous and quick.