|

| Jeff Wall in his studio. |

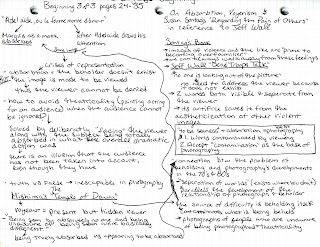

Fried's book, interestingly enough, has three beginnings. Each beginning deals with different issues that have arisen out of the viewer-photograph relationship.

The first beginning talks about how Hiroshi Sugimoto's Movie Theaters cannot be understood to their fullest potential without the understanding of his contemporaries work, specifically those of Jeff Wall and Cindy Sherman, who both were investigating the nature of cinema and photography.

First Fried tackels Cindy Sherman and her Untitled Film Stills series. Here he clearly lays a path that he will continue to pace over until the theoretical carpet is worn- absorption is the only way art can function. With that comes a lot of explanation of how absorption is created, perceived and not perceived. At this point is suffices to say that Sherman's works apply an absorptive method within which the viewer is denied communication with the photographic subject. (i.e. Sherman looks away from the camera lens in every image as she appears to be drawn to another object within the frame.)

Next, we take a look at Jeff Wall and specifically his images associated with Movie Audience. These images are meant to be indicative of an audience watching a movie. Wall's argument on cinema is that the audience is not watching a product but rather the making of the product and the only recognition of this situation comes from trying to forget it. In other words, an audience attempts to forget its own existence while watching a movie.

And while Fried agrees with this idea, he also adds that cinema has the ability to escape theatricality, or rather it provides a refuge from it rather than defeat it and so Fried concludes that cinema is not and cannot be a modernist art. However, the use of cinematic forces through photography has merit in attempting to solve the problem of theatricality.

This is where Fried draws his connection between Sugimoto and Wall. Fried writes that perhaps the Movie Audience is the missing audience from Sugimoto's Movie Theaters. And while that is done all tongue and cheek, the main idea is that both audiences seem to have "forgotten themselves in the machine."

Still, for Sugimoto's series, that is not what is most important, but rather the lack of the movie audience brings with it a detachment on the side of the viewer. This detachment occurs because the viewer has no sense of belonging to that audience and so it potentially allows two things to occur: the developing of a theoretical discussion and the aesthetically pleasing nature of the image itself to be taken into account. Fried clearly pushes the discussion angle, but does note that both of these work together in a photograph.

The second beginning of the book discusses the idea of the Tableau in art photography in reference to Jeff Wall, Thomas Ruff, Stephen Shore and with a heavy hand on Jean Marc Bustamante. Here again he reiterates the shift in photography from small black and white prints to large, colorful, wall-hanging images. Jeff Wall again shows up as an important figure who explores tactics of absorption through heavily detailed imagery (The Destroyed Room) and the idea of a viewer's response to a moment of viewing (Picture for Women). It should also be noted that both of these photographs previously mentioned make reference to traditional French paintings that were of the same scale.

|

| Jean-Marc Bustamante, Tableau no. 103 and Tableau no. 104 |

In contrast to all of this, Stephen Shore's photographs, through the differentiated use of color, light, etc.(clearly the same tools used by Bustamante), always allow the viewer into the image.

The third beginning of the book takes a little bit of a different turn in that is uses two stories as examples towards understanding absorption and theatricality. The first is titled Adelaide, ou la femme morte d'amour. After the story Fried begins to outline the most interesting part of the story for himself, the instance where the main man of the story is absorbed in what he is doing and the second instance where he knows his love is watching and trying to get his attention but pretends to continue to be absorbed. According to Fried, both of the "images" look the same but are not, and that is where a crisis of representation occurs. This crisis might better be stated in Fried's terms, where absorption (how art must function) means that the beholder cannot exist, but must exist because these images were made to be beheld. In order to solve this crisis, art must now create an illusion that the audience has not been taken into account, although they have been.

The second story is titled The Temple of Dawn. Here we look at voyeurism and its inherent character the voyeur, a present but hidden viewer. Here there is a quick connection to the previous story in that at one point the main character states that "Being seen by absolutely no one and being unaware of being seen were basically different." which again brings up the crisis of representation. What Fried means for us to grasp from this story is that there was a development in which the problem with beholding an image became the act of beholding. Not through this story in particular, but over art theory and time it was realized that as we look at an image we "contaminate" it with our own perceptions and that the work can never truly exist in a pure form without the "death" of the viewer.

|

| Detail from Jeff Wall's Dead Troops Talk |

In the end, Fried once again argues that "Diderotian" themes of absorption has been infused into what he considers to be the most interesting and important photography. Finally, through the connection made with The Temple of Dawn, we begin to understand that for Fried, photography has become the only medium that has accepted the contamination aspect of looking and has begun to use it as part of its own design.

Other research and links:

Art History Unstuffed- Denis Diderot

Photographic Voyeurism Exhibit

New York Times on Jeff Wall

Hiroshi Sugimoto's Website

No comments:

Post a Comment